Myeloneuropathy with Bilateral Foot Pain after Scrub Typhus Infection: An Antibody-Proven Case Report

Article information

Abstract

Scrub typhus is an acute febrile illness caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi. The most common neurological symptoms are headaches presenting with meningitis, meningoencephalitis, or encephalitis; however, transverse myelopathy and polyneuropathy are rare in typhoid infections. Herein, we report a laboratory and electrodiagnostically proven case of subacute myelopathy and polyneuropathy with slow progression after scrub typhus infection. A 64-year-old man complained of truncal numbness and a burning sensation in both feet. Magnetic resonance imaging did not reveal any definite changes in the spinal cord; however, serological tests showed immunoglobulin G antibodies against O. tsutsugamushi by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. An electrophysiological study showed myelopathy concurrent with polyneuropathy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first immunochemical detection of antibodies in a patient with delayed neurological manifestations after scrub typhus infection.

Introduction

Scrub typhus is an acute febrile illness caused in Southeast Asia by rickettsial infection mediated by the bite of larvae infected with Orientia tsutsugamushi. The most common neurological symptoms are headaches presenting with meningitis, meningoencephalitis, or encephalitis [1]. However, transverse myelopathy and polyneuropathy are rare in typhoid infections. Simultaneous involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system is extremely rare [2]. Post-infectious neurological manifestations may arise from an autoimmune phenomenon, as a result of direct infection and as a sequela of the infection. In addition, confirmation through serological tests in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and post-infectious deterioration in the subacute period have not been reported.

We report a case of subacute myelopathy simultaneously accompanied by polyneuropathy resulting from scrub typhus infection, which was confirmed by laboratory antibody testing and responsive to steroid therapy.

Case Report

A 64-year-old man visited a neurology clinic with truncal numbness and a burning sensation in both feet. He had no underlying medical conditions, such as diabetes, alcohol abuse, or vitamin deficiency. He had been admitted to the Department of Infective Medicine at another hospital because of fever and eschar on his right ankle after field activities 2 months ago. He was diagnosed with scrub typhus and empirically treated with doxycycline and steroids as the standard treatment for 1 week after diagnosis. At the time of discharge , the patient did not notice any symptoms. About 1 month before visiting our clinic (3 weeks after discharge), he had progressive pain in his legs, especially in both feet, numbness in his trunk, and difficulty in defecation, with decreased sensation in the groin and inguinal area. He had gait disturbance with pain and a floating sensation while standing and walking on the ground. He was noted to have a subacute eschar on his right ankle and no fever(Fig. 1). A neurological examination revealed a well-defined truncal sensory level at T4, below which the sensation of pain and temperature was markedly decreased. On both legs, especially the feet, he felt allodynia on touch sensation. Proprioception was impaired and Romberg’s sign was positive. He showed a high stepping gait that significantly worsened when he closed his eyes. No motor weakness was noted in either the upper or lower extremities; however, the deep tendon reflex was absent in the bilateral knee and ankle, while the upper extremities showed an intact deep tendon reflex. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed no definite changes in signal intensity throughout the spinal cord (Fig. 2). CSF cytology results were normal. Serological tests showed immunoglobulin G antibodies to O. tsutsugamushi by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

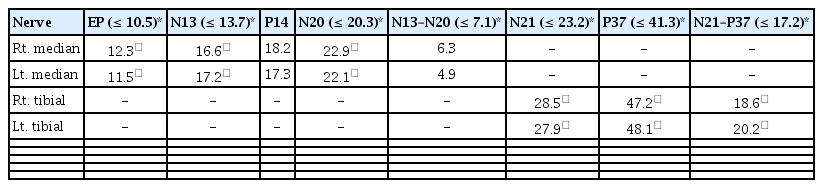

Nerve electrophysiological studies supported the presence of myelopathy concurrent with polyneuropathy, and nerve conduction studies revealed severe sensory-dominant axonal polyneuropathy (Table 1). Sensory evoked potentials demonstrated a central conduction delay (Table 2) [3]. To exclude other inflammatory demyelinating diseases, we checked for oligoclonal bands in the CSF, serum anti-ganglioside antibodies, and anti-aquaporin-4 antibodies, all of which were negative. Immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G for O. tsutsugamushi were detected in the CSF. Intravenous steroid therapy (1 g/day) was administered for 5 days. After treatment, the numbness, allodynia, pain, and decreased sensation in both legs improved at the time of discharge.

Nerve Conduction Study Showing Severe Sensory-Dominant Axonal Polyneuropathy upon Visiting the Neurology Department

Written informed consent by the patients was waived due to a retrospective nature of our study.

Discussion

Scrub typhus is a rickettsial infection mediated by the bite of larvae infected with O. tsutsugamushi. It is known to occur throughout the Asia-Pacific region, including in Korea [4]. An eschar at the site of the bite may help in the diagnosis. Common symptoms of scrub typhus include fever, conjunctival injection, headache, myalgia, and gastrointestinal symptoms [5]. The symptoms and complications vary widely among patients, and some may suffer from neurological symptoms. O. tsutsugamushi can invade the CSF and is considered a cause of mononuclear meningitis. The symptoms are similar to those of leptospirosis, viral meningitis, and tuberculous meningitis [6]. It can also invade the blood vessels in the CNS, which can cause vasculitis [7]. Neurologic manifestations of scrub typhus include altered sensorium, headache, seizures, ataxia, double vision, hyperpyrexia with stiffness of the whole body, and acute bilateral lower limb weakness [8]. Spinal MRI findings may show focal and central high-signal regions extending to three or four segments in the T2 sequence. However, the MRI findings are normal in 40% of cases. In our case, the MRI findings were normal, but they could be differentiated from compressive myelopathy [9].

This is the first immunochemically detected case of delayed neurological manifestations of both myelopathy and polyneuropathy after scrub typhus infection. The detection of O. tsutsugamushi using ELISA showed good sensitivity (94%) and specificity (91%) [10]. Clinical features, electrophysiological studies, and serological studies suggested an association of typhoid infection with thoracic myelopathy and sensory-dominant axonal polyneuropathy. When a patient complains of numbness in the trunk and a burning sensation in both feet, it may be necessary to recognize the neurological symptoms of delayed typhoid and consider it in the differential diagnosis in order to ensure an accurate diagnosis and proper management.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.