Severe Isolated Peripheral Polyneuropathy without Myelopathy after Nitrous Oxide Abuse: A Case Report

Article information

Abstract

Nitrous oxide (N2O) abuse induces vitamin B12 deficiency, resulting in complications in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Some cases related to subacute combined degeneration or myeloneuropathy after N2O abuse have been reported. However, isolated peripheral polyneuropathy without spinal cord involvement has rarely been reported in South Korea. We describe a 29-year-old woman who had inhaled “happy balloons” daily (1,000 balloons/day) for recreational purposes over 3-month period, and presented with acute symmetrical hypoesthesia, paresthesia, and motor weakness on the bilateral lower limbs. Serologic tests showed megaloblastic anemia and vitamin B12 deficiency. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and spine showed no abnormalities. An electrodiagnostic study confirmed lower limb–dominant axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy due to vitamin B12 deficiency from N2O abuse. The patient was treated with intramuscular vitamin B12 replacement. A follow-up electrodiagnostic study 4 months after the initial study showed only partial improvement. Despite the legal efforts of the Korean government to ban the use of N2O other than for medical purposes, cases of complications from its abuse are on the rise, especially among young adults. Physicians should recognize the strong possibility of N2O abuse as an underlying cause of vitamin B12 responsive polyneuropathy with or without spinal cord involvement.

Introduction

Nitrous oxide (N2O) has been used historically for anesthetic purposes in medical treatment for a long time. However, an increasing number of young adults misuse so-called “happy balloons” as a way to consume this gaseous agent for recreational purposes, resulting in various medical complications among abusers. N2O is known to inactivate vitamin B12, interfering with the methionine synthase cycle, which is vital for stabilizing the myelin sheath. Cases have been reported in the literature of vitamin B12 deficiency leading to axonal degeneration and demyelination in both the central and peripheral nervous systems, ultimately resulting in subacute combined degeneration (SCD) or myeloneuropathy [1–5]. In South Korea, isolated peripheral polyneuropathy (PN) induced by N2O abuse without myelopathy has been rarely reported; moreover, detailed electrodiagnostic study data and information on the associated amount of inhalation have also been deficient [3]. Herein, we report a case of a patient who developed isolated acute sensorimotor axonal PN after heavy N2O intoxication, including electrodiagnostic study findings. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Presbyterian Medical Center (approval number: E2022-09).

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman with history of clinical depression presented to our department with a 3-month history of symmetrical hypoesthesia, paresthesia, and motor weakness of the bilateral lower limbs. She complained of voiding difficulty along with intermittent fecal incontinence; and required assistance in ambulating due to gait disturbance. In general, the patient was in otherwise good health. Her social history showed that she worked as a professional cheerleader and had engaged in a daily habit of inhaling “happy balloons” (total usage: 1,000 balloons) for 3 months until the sudden presentation of the aforementioned symptoms. The patient’s past medical history was significant for a recent short-term inpatient admission at another hospital due to poor oral intake accompanied by episodes of melena with epigastric pain, which was treated with a proton pump inhibitor.

On a manual muscle test, motor weakness was evident on ankle dorsiflexion (grade: 1 out of 5), plantarflexion (grade: 2 out of 5), and in other lower limbs (grade: 3 out of 5) bilaterally and symmetrically, while the upper limbs were both normal (grade 5 out of 5). Pain and temperature sensation were normal, but the sense of light touch and pinprick was markedly reduced below the bilateral knees. Deep tendon reflexes at the bilateral ankles were diminished. Although the patient required assistance during ambulation, her coordination was normal; there were no pathologic reflexes nor Lhermitte’s sign, and Romberg’s test was negative.

The initial serologic test showed anemia and vitamin B12 deficiency: hemoglobin, 8.0 g/dL (normal range, 12–16 g/dL); red blood cell count, 2.61 × 106/mm3 (normal range, 3.8–5.4 × 106/mm3); mean corpuscular volume, 91 fL (normal range, 79–100 fL); and vitamin B12, 135.8 pg/mL (normal, 197–771 pg/mL). The vitamin B9 level was normal (5.6 ng/mL; normal range, 3.9–26.8 ng/mL). Follow-up laboratory testing performed after 2 weeks showed a hemoglobin level of 9.4 g/dL (normal range, 12–16 g/dL), a red blood cell count of 2.87 × 106/mm3 (normal range, 3.8–5.4 × 106/mm3), a mean corpuscular volume of 102 fL (normal range, 79–100 fL); and a peripheral blood smear consistent with megaloblastic anemia. Brain and full-spine T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging was negative, excluding any evidence of cervical nervous system involvement. Urodynamic studies, assessments of anal contraction, deep anal pressure, and perianal sensation could not be elucidated as the patient declined these components of a comprehensive physical examination and diagnostic workup.

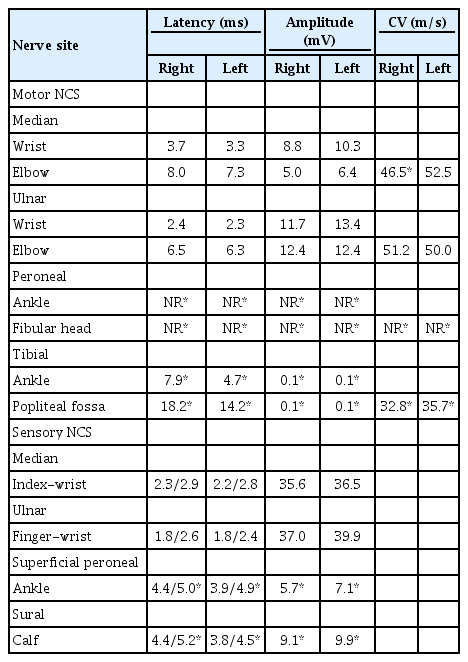

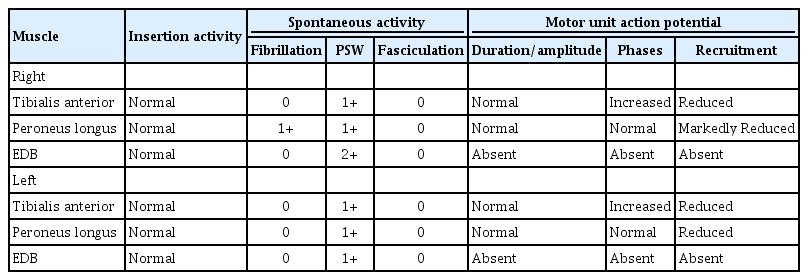

An electrodiagnostic study was performed 3 months after the initial onset of symptoms. Motor nerve conduction studies (NCS) demonstrated delayed onset latencies and low amplitudes for the bilateral tibial and right median compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) with decreased nerve conduction velocities. The bilateral peroneal CMAPs were unobtainable. Sensory NCS showed delayed latencies and low amplitude of bilateral superficial peroneal and tibial sensory nerve action potentials (Table 1). F-wave, H-reflexes, and evoked potentials were not tested due to patient's poor compliance with the study. Needle electromyography (EMG) demonstrated abnormal spontaneous activity (ASA) and decreased interference patterns in both tibialis anterior and peroneus longus muscles, and ASA with unobtainable motor unit action potentials in both extensor digitorum brevis muscles (Table 2). The results of the test were compatible with severe sensorimotor PN (mainly axonal injury) involving the lower extremities.

To treat her vitamin B12 deficiency, the patient received daily intramuscular injections of 1 mg of vitamin B12 (Actinamide; Shin Poong Pharm Inc., Ansan, Korea) for 7 days, with recommendations to taper down to once a week for a month and lifelong maintenance of monthly injections along with 1 mg of oral cyanocobalamin supplement (Vitamedin; HK innoN, Seoul, Korea). The patient’s serum vitamin B12 level after 3 months of supplementation increased to 539.1 pg/mL (normal range, 197–771 pg/mL). As the patient refused an assessment of voiding difficulty, her subjective symptoms of urgency with hesitancy were managed pharmaco-therapeutically, using a cholinergic agonist, which led to partial resolution of these urinary symptoms.

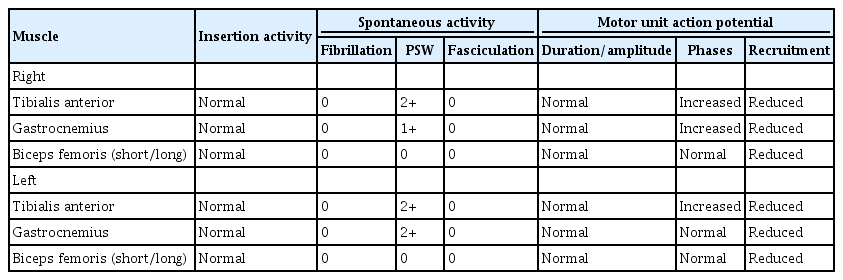

Seven months after the initial onset of symptomatology, motor strength in ankle dorsiflexion showed partial improvement from grade 1 to 2, while a sensory examination, including proprioception, remained abnormal. However, the patient could walk without assistance using bilateral foot orthoses. In a follow-up electrodiagnostic study, there was no significant improvement. Bilateral peroneal and tibial CMAPs were unobtainable; the bilateral superficial peroneal muscles showed prolonged amplitudes and latencies, while the tibial muscles continued to show no response on NCS (Table 3). Needle EMG demonstrated ASA in both the tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles (Table 4). The result was still consistent with known sensorimotor PN (mainly axonal injury) involving the lower extremities.

Discussion

Vitamin B12 is a cofactor for methionine synthase and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, which are involved in the production of DNA and myelin. N2O, by inactivating cobalamin, interferes with the methionine synthase cycle and affects both the central and peripheral nervous systems, resulting in demyelination and axonal degeneration of the dorsal and lateral columns of the spinal cord, white matter in the brain, peripheral, and cranial nerves [6]. Bouattour et al. [7] reported that patients with vitamin B12 deficiency showed sensorimotor neuropathy, mainly of the axonal type, with demyelinating features as the major electrodiagnostic findings.

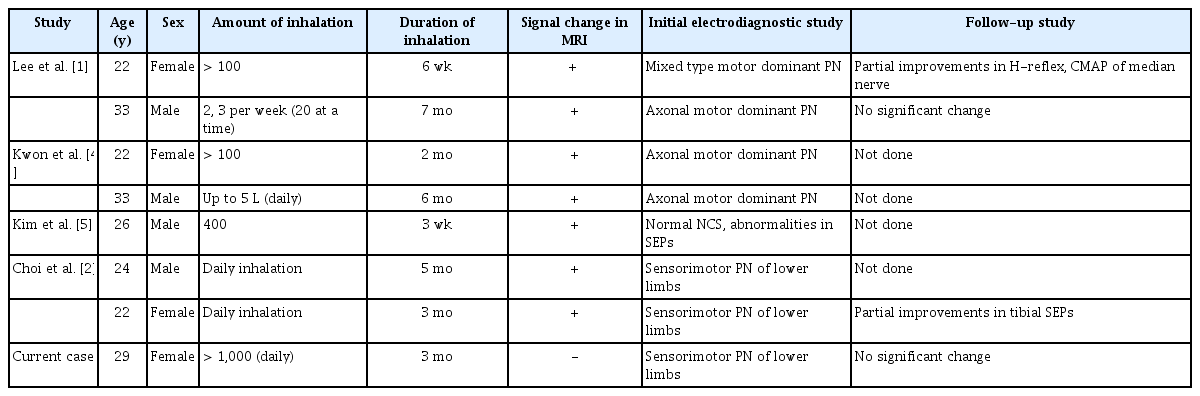

Patients who engage in N2O abuse often complain of acute onset of motor weakness and hypoesthesia, which are more severe in the distal lower limbs, and this pattern appears to be associated with electrodiagnostic study findings of axonal sensorimotor neuropathy mainly in the lower extremities in a dose-dependent manner [8–10]. Our patient had an admitted history of daily inhalation, totaling 1,000 happy balloons, for 3 months with sudden evident motor and sensory deficits, likely attributable to axonal sensorimotor PN in the lower extremities. Interestingly, our case showed no involvement of the central nervous system on imaging. Lee et al. [3] reported two cases of isolated PN from N2O intoxication; however, the duration of intoxication was within a month, no information was presented regarding the amount of inhalation, and sensory rather than motor symptoms were the chief complaint.

In determining the main cause for vitamin B12 deficiency in our case, several limitations are considered. These include (1) the patient’s history of taking a proton pump inhibitor to address the episode of melena; (2) poor intake during the gaseous agent abuse period, which could have also contributed to low vitamin B12 levels; and (3) failing to check serum levels of homocysteine and methylmalonic acid, which can also reflect deficiency levels. However, vitamin B12 deficiency is known to be related to long-term adherence to a strict vegan diet and prolonged use of proton pump inhibitors. Our patient had a history of a significantly higher amount of N2O than other reported cases of SCD from N2O abuse in Korea, as presented in Table 5 [1,2,4,5]. Considering the amount of gas inhalation and the acute onset of presentation of sensorimotor impairment in our patient, we can infer that N2O abuse was a major factor contributing to vitamin B12 deficiency in this patient.

N2O abuse has long been a social issue in Korea. After escalating overuse and deaths associated with its abuse, in 2017 the Korean government banned the use of N2O other than for medical purposes, as was the case in the United Kingdom under the Psychoactive Substances Act in 2016. Despite legal efforts, case studies related to the harmful effects of N2O abuse continue to be reported, and there is likely to be a larger public health crisis involving victims of N2O abuse among young adults in their 20s and 30s (Table 5), who are unaware of the potentially serious complications of abuse.

In conclusion, our report presents a case of isolated sensorimotor PN of the lower extremities following a short period of N2O abuse. Clinicians should suspect and firmly consider the underlying possibility of N2O abuse to prevent serious complications, especially in young adults presenting with vitamin B12 deficiency PN, and actively promote efforts to improve social awareness of its abuse as a potential public health crisis.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.