Introduction

Femoral nerve originate from the L2, L3, and L4 nerve roots. It has muscular branches in the psoas, iliacus, quadriceps femoris, sartorius, and pectineus muscles, as well as thigh medial and intermediate cutaneous nerves and saphenous nerves. Isolated femoral neuropathy rarely occurs due to abdomen, hip, or pelvis surgery or stretch stress, compression by hematoma, tumor, abscess. Spontaneously occurring femoral neuropathy in young men is very rare, and bilateral cases have not been reported. We report a case of spontaneous bilateral femoral neuropathy with literature review.

Case Report

A 25-year-old man suffering from depression was admitted to the Department of Neuropsychiatry for drug intoxication and was accompanied by weakness of bilateral knee extensors. He has been taking depression medications (procyclidine, lamotrigine, lorazepam, quetiapine, sertraline, escitalopram, propranolol) for several years. He enlisted in the army recruit training center for military service ten days before visiting the hospital, and took about ten bags of psychiatric medication for stress and slept for a day. Sleep was done in the supine position, and postures such as the hip extension were not confirmed. After he woke up, he suddenly complained of weakness and pain in both lower extremities and checked out the army recruit training center because he was unable to walk. Afterward, he suffered sleep disorders and suicidal thoughts and was admitted to the Department of Neuropsychiatry. In the blood test, creatine phosphokinase showed a mild elevation of 214 IU/L (normal range, 60-190 IU/L), and other abnormalities were not observed. On physical examination, there was no bruise, swelling, pain, or tenderness on the flank, abdomen, buttocks and thigh that would suspect trauma. Neurological examination showed that measurement of manual strength of right hip with hip flexion 4/5, extension 4/5, right knee with knee flexion 4/5, extension 3/5, left hip with hip flexion 3/5, extension 4/5, and left knee with knee flexion 4/5, extension 2/5. On the 13th days of symptoms, nerve conduction study (NCS) and needle electromyography (EMG) were performed. In the sensory NCS, the bilateral saphenous nerve sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) did not appear, and in the motor NCS, the left femoral nerve compound muscle action potential (CMAP) did not appear. When measured on the extensor digitorum brevis muscle, there was a decrease in the CMAP amplitude of both common peroneal nerves, which was considered to be due to disuse atrophy or focal atrophy (

Tables 1,

2). Abnormal spontaneous activity was observed in bilateral adductor magnus, rectus femoris, vastus medilais, and left vastus medialis, and no motor unit action potential was observed in left rectus femoris, vastus medialis (

Table 3). Taking electromyographic findings and clinical findings together, ŌĆśbilateral femoral neuropathy, left side more severely involvedŌĆÖ was diagnosed.

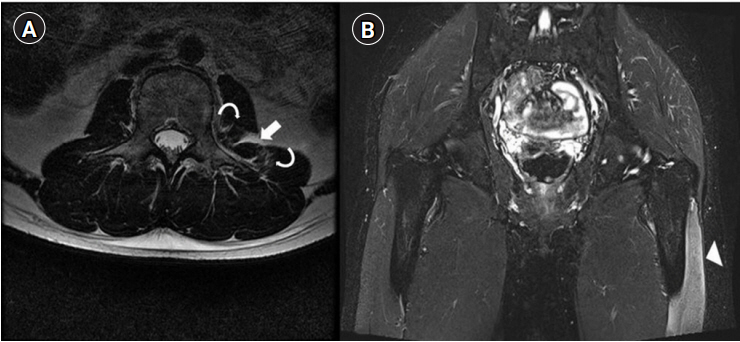

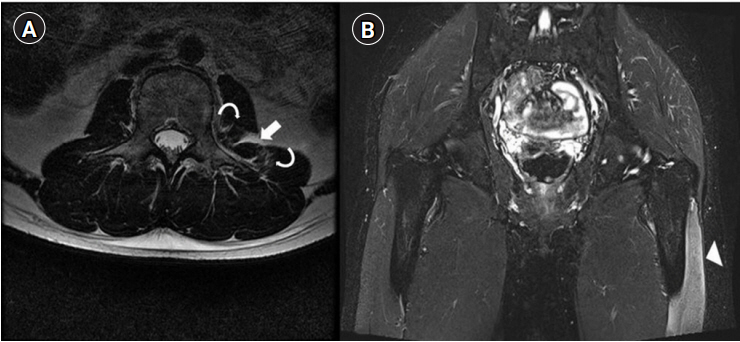

Follow-up EMG was performed on the 59th day of symptom onset and showed little interval change compared to the previous test. Thoracic and lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to differentially diagnose radiculopathy on the 10th day. It showed increased signal intensity in T2 weighted image between left psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles, suggesting hematoma. In addition, there was high signal intensity indicating focal muscle fiber tear and strain in both muscles in T2 weighted image. Due to cost problem, tests were selectively performed in the early period. As weakness persisted, hip MRI was performed late for differential diagnosis on the 82nd day of symptom development to check femoral nerve and to identify other lesion that may cause neuropathy. It showed no abnormality of lumbosacral plexus and proximal sciatic nerve, but signal intensity change was observed in the left vastus intermedius, vastus lateralis, psoas, and pectineus muscles (

Fig. 1). Hematoma was treated conservatively. After three months of symptom onset, muscle strength of right knee extension improved 3/5 to 4/5 in the outpatient clinic observation, but there was still difficulty in walking and stair up and down due to muscle weakness, and bilateral anterior thigh muscle atrophies, left side dominant, were observed (

Fig. 2).

On the 204th day of symptom development, a third follow up EMG was performed, and the SNAP of the bilateral saphenous nerve, which was not previously induced, was observed. In needle EMG, the loss of denervation potential on the right side and some improvement on the left rectus femoris were also observed (

Table 3). After about 13 months of weakness, muscle strength of left knee extension improved from 2/5 to 3/5, and the gait restriction disappeared when observed in the follow-up outpatient department.

Discussion

The femoral nerve originates from the L2, L3, and L4 nerve roots and travels between the psoas and iliacus muscles, located under the iliacus fascia in a retroperitoneal space and then under the inguinal ligament. Motor branches innervate to muscles such as iliacus, quadriceps, and sartorius, and sensory branches are responsible for the sense of anterior, medial area of the thigh, and lower leg medial area. Isolated femoral neuropathy is uncommon and rarely occurs bilaterally. Femoral nerve injury can be caused by compression or entrapment, mainly in retroperitoneal space and inguinal ligament [

1]. Femoral neuropathy may cause pain in the inguinal, femoral, and lower abdomen, and pain exacerbation may occur with hip movement. The hip flexor, knee extensor weakness, and gait disturbance may be accompanied, and hypoesthesia occurs in the thigh anterior, medial part, and lower leg medial part.

Femoral neuropathy rarely occurs, and to our knowledge, no spontaneous case has been reported. The reported causes of femoral neuropathy can be classified as traumatic/nontraumatic injury or surgery/non-surgery injury. Surgery-related etiology has been reported such as vaginal hysterectomy, radical retropubic prostatectomy, laparoscopic vaginal surgery, and suggested mechanisms include microvascular injury, compression by retractor, and mechanical stretch due to posture during surgery [

2-

4]. Non surgery etiology includes blunt trauma, hematoma, rhabdomyolysis, suicide attempt after anticoagulant use. Nerve compression and excessive stretch such as hanging leg syndrome have been suggested as mechanisms [

5-

9]. Mechanisms such as ischemia, compression, and stretch have been suggested to cause nerve injury regardless of etiology.

In this case, symptoms occurred after an overdose of the drug. Radiculopathy can also be considered as the cause of knee extensor weakness, but it was excluded from the electrical diagnosis. In a similar case to this case, bilateral femoral neuropathy occurred after massive toxic ingestion in order to commit suicide. It was considered that stretch injury occurred due to improper position [

7]. Other mechanisms that should be considered to cause nerve injury are compression and ischemia. In other case, bilateral femoral neuropathy also occurred after drug overuse. It is thought that compression in the inguinal area or stretch injury was caused by maintaining knee flexion, hip flexion, and hip external rotation posture [

8]. In this case, the patient maintained the supine position, and there was no cause for stretch injury or nerve compression by position. A small loculated hematoma was found between the left psoas and quadratus lumborum on the MRI scan, but it was thought to be small, not enough to cause compressive neuropathy. The risk factors for hematoma include coagulation disorder, renal, cardiac, hepatic insufficiency, and anticoagulant therapy. Renal and hepatic insufficiency were not observed in the laboratory test performed at the time of hospitalization and he did not receive anticoagulant therapy. There were no tests for coagulation disorder and cardiac insufficiency. Secondary nerve damage caused by vasculitis or vascular disease is not completely excluded due to the absence of angiographic computed tomography or MRI, but no inflammatory sign was found in laboratory findings, and no other signs or symptoms were observed. The bilateral femoral neuropathy in this case report is assumed to be spontaneous onset and is considered to be related to critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP). The pathophysiology of CIP is not yet clear, but microvascular alteration, metabolic alteration, and electrical alteration are known to be involved. CIP is a length-dependent axonal polyneuropathy, showing a decrease in the amplitude of SNAP and CMAP. It may be asymmetric and more severe in the lower extremities than in the upper extremities [

10].

We report bilateral femoral neuropathy that occurred spontaneously without specific mechanisms after drug intoxication through hip MRI, NCS, and needle EMG [

2-

9].

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Fig.┬Ā1.

T2-weighted magnetic resonance image showing high signal intensity of a loculated hematoma (arrow) between the psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles, a focal irregular discontinuity with feathery-like high signal intensity of a focal muscle fiber tear, and strain in the left psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles (curved arrows) (A), and a high-signal-intensity lesion (arrowhead) in the left vastus lateralis muscle (B).

Fig.┬Ā2.

Clinical photography showing atrophy of the left quadriceps muscle, especially the vastus medialis muscle (arrows). The case report and patientŌĆÖs photographs were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Catholic University of Korea, College of Medicine (Registry No. VC14ZISE0072); the requirement for informed consent was waived by the board.

Table┬Ā1.

Results of Sensory Nerve Conduction Studies

|

Nerve |

Stimulation |

Initial (13 HD)

|

Follow-up (204 HD)

|

|

Peak latency (ms) |

Amplitude (╬╝V) |

CV (m/s) |

Peak latency (ms) |

Amplitude (╬╝V) |

CV (m/s) |

|

Rt. sural |

Lower leg |

3.8 |

12 |

47.9 |

3.6 |

13.9 |

49.2 |

|

Lt. sural |

Lower leg |

3.7 |

21.6 |

49.6 |

3.6 |

19.9 |

50.3 |

|

Rt. superficial peroneal |

Ankle |

3.9 |

12.4 |

46.6 |

4.1 |

7.9 |

45.1 |

|

Lt. superficial peroneal |

Ankle |

3.3 |

18.4 |

45.4 |

3.9 |

12.1 |

45.1 |

|

Rt. saphenous |

Knee |

No response |

2.7 |

6.8 |

70.0 |

|

Lt. saphenous |

Knee |

No response |

3.0 |

3.7 |

66.6 |

|

Rt. LFCN |

Above inguinal ligament |

2.9 |

12.3 |

-┬Ā |

4.4 |

18.0 |

- |

|

Lt. LFCN |

Above inguinal ligament |

2.9 |

8.6*

|

- |

3.0 |

7.6*

|

- |

Table┬Ā2.

Results of Motor Nerve Conduction Studies

|

Nerve |

Stimulation |

Initial (13 HD)

|

Follow-up (204 HD)

|

|

Onset latency (ms) |

Amplitude (mV) |

CV (m/s) |

Onset latency (ms) |

Amplitude (mV) |

CV (m/s) |

|

Rt. femoral |

Above inguinal ligament |

5.9 |

9.4 |

- |

7 |

9.9 |

- |

|

Lt. femoral |

Above inguinal ligament |

No response |

|

|

No response |

|

|

|

Rt. peroneal (EDB) |

Ankle |

4.2 |

0.5*

|

- |

4.6 |

0.4*

|

- |

|

Fibular (head) |

10.8 |

0.8*

|

48.4 |

12.5 |

0.4*

|

41.1 |

|

Lt. peroneal (EDB) |

Ankle |

3.7 |

1.4*

|

- |

4.5 |

|

- |

|

Fibular (head) |

10.1 |

0.9*

|

50.0 |

13.3 |

3.6 |

39.7 |

|

Rt. peroneal (TA) |

Fibular (head) |

2.9 |

4.9 |

- |

2.7 |

6.1 |

- |

|

Popliteal fossa |

3.7 |

4.8 |

113.0 |

4.0 |

6.0 |

61.5 |

|

Lt. peroneal (TA) |

Fibular (head) |

2.2 |

4.6 |

- |

3.1 |

5.9 |

- |

|

Popliteal fossa |

3.5 |

4.5 |

53.8 |

4.7 |

5.4 |

65.6 |

|

Rt. tibial |

Ankle |

5.1 |

28.9 |

- |

4.8 |

17.7 |

- |

|

Popliteal fossa |

12.1 |

24.5 |

42.1 |

11.9 |

13.4 |

50.7 |

|

Lt. tibial |

Ankle |

4.1 |

24.2 |

- |

4.1 |

15.1 |

- |

|

Popliteal fossa |

10.9 |

18.8 |

44.1 |

11.4 |

11.2 |

47.2 |

Table┬Ā3.

Results of Needle Electromyography

|

Muscle |

Initial (13 HD)

|

Follow-up (204 HD)

|

|

IA |

Fib |

PSW |

MUAP |

Interfer. |

IA |

Fib |

PSW |

MUAP |

Interfer. |

|

Both L2-S1 PSP |

NL |

None |

None |

|

|

NL |

None |

None |

|

|

|

Both TFL |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

NT |

|

Both AL |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

|

Both TA |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

NT |

|

Both PL |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

NT |

|

Both GCM (medial) |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

NT |

|

Rt. AM |

NL |

None |

1+ |

NL |

Full |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

|

Rt. GMax |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

|

Rt. iliopsoas |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

|

Rt. RF |

NL |

1+ |

2+ |

Poly |

Discrete |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Discrete |

|

Rt. VM |

NL |

None |

1+ |

Poly |

Discrete |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Discrete |

|

Rt. BF |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

NT |

|

|

|

|

|

Lt. AM |

NL |

None |

1+ |

NL |

Full |

NL |

None |

1+ |

NL |

Full |

|

Lt. GMax |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Poor volition |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

|

Lt. iliopsoas |

NL |

1+ |

2+ |

NL |

Reduced |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Full |

|

Lt. RF |

NL |

None |

2+ |

No MUAP |

|

NL |

None |

2+ |

Poly |

Full |

|

Lt. VM |

NL |

None |

1+ |

No MUAP |

|

NL |

1+ |

3+ |

No MUAP |

|

|

Lt. BF |

NL |

None |

None |

NL |

Poor volition |

NT |

References

1. Bowley MP, Doughty CT: Entrapment neuropathies of the lower extremity. Med Clin North Am 2019;103:371-382.

2. Hsieh LF, Liaw ES, Cheng HY, Hong CZ: Bilateral femoral neuropathy after vaginal hysterectomy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:1018-1021.

3. Roth JV: Bilateral sciatic and femoral neuropathies, rhabdomyolysis, and acute renal failure caused by positioning during radical retropubic prostatectomy. Anesth Analg 2007;105:1747-1748.

4. Damario MA, Holcomb K, Bodack MP: Bilateral femoral neuropathy complicating a combined laparoscopic-vaginal procedure. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1996;4:69-72.

5. D'Amelio LF, Musser DJ, Rhodes M: Bilateral femoral nerve neuropathy following blunt trauma. Case report. J Neurosurg 1990;73:630-632.

6. Pu├®chal X, Liot├® F, Kuntz D: Bilateral femoral neuropathy caused by iliacus hematomas during anticoagulation after cardiac catheterization. Am Heart J 1992;123:262-263.

7. Mathis S, du Boisgu├®heneuc F, Goden├©che G, Ansquer S, Neau JP: Bilateral femoral neuropathy after massive toxic ingestion in a suicide attempt. Neurologist 2012;18:70-72.

8. Tsiptsios D, Daud D, Tsamakis K, Rizos E, Anastadiadis A, Cassidy A: Bilateral femoral neuropathy: a rare complication of drug overdose due to prolonged posturing in lithotomy position. Case Rep Neurol Med 2020;2020:235285.

9. Rottenberg MF, DeLisa JA: Severe femoral neuropathy with "hanging leg" syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1981;62:404-406.

10. Shepherd S, Batra A, Lerner DP: Review of critical illness myopathy and neuropathy. Neurohospitalist 2017;7:41-48.